DVT/PE Risk Assessment Tool

Personal Risk Assessment

Answer the following questions about your health factors to estimate your DVT/PE risk level.

Your Risk Assessment Results

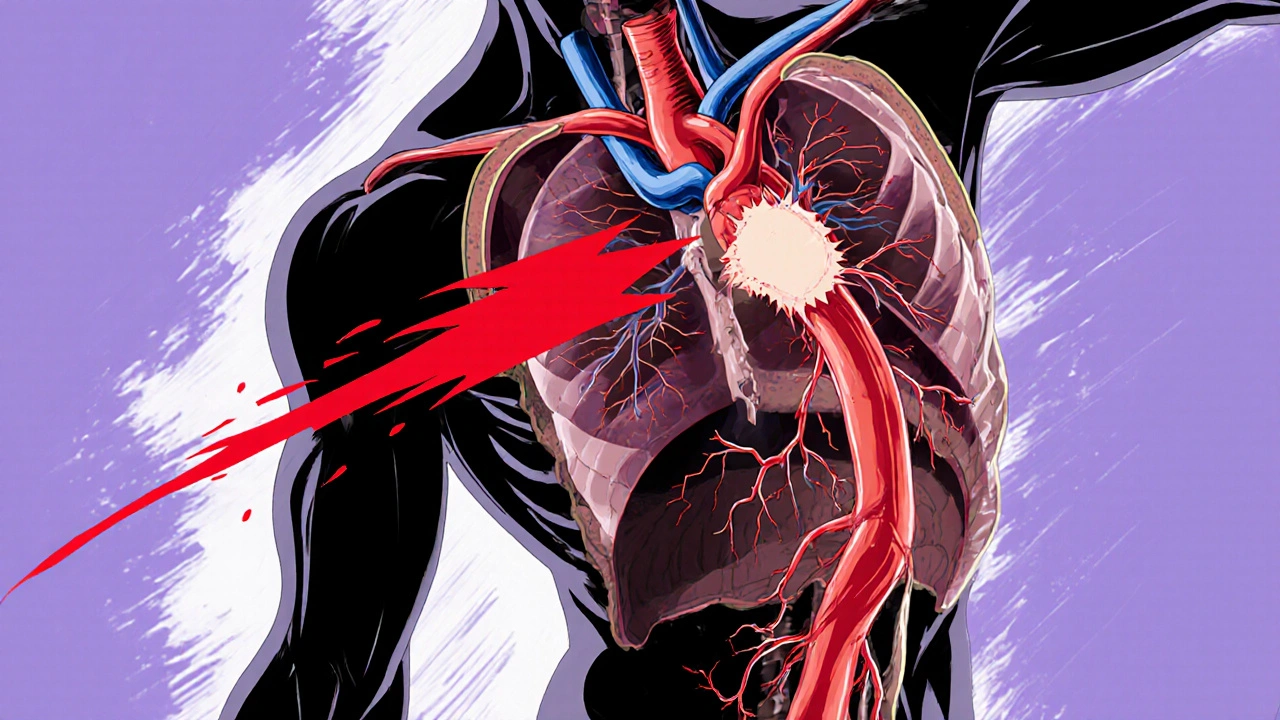

When a blood clot forms in a leg vein and then jumps to the lungs, the consequences can be life‑changing. Deep Vein Thrombosis is a dangerous clot that develops in the deep veins of the lower limbs, usually after periods of inactivity or injury. If that clot breaks free, it travels through the venous system and can lodge in the pulmonary arteries, causing a Pulmonary Embolism - a blockage that prevents oxygen‑rich blood from reaching the lung tissue. Understanding how these two conditions interact helps you spot warning signs, get the right diagnosis, and take steps to keep the clot from moving.

What Is Deep Vein Thrombosis?

DVT occurs when a blood clotA semi‑solid mass of fibrin, platelets, and trapped blood cells that forms in a vein builds up in the deep veins, most often in the thighs or calves. The clot may be small and cause no symptoms, or it may swell the leg, create pain, and make the skin feel warm.

- Typical locations: femoral, popliteal, and iliac veins.

- Key triggers: prolonged sitting (flights, long drives), surgery, trauma, and certain cancers.

- Underlying mechanisms: reduced blood flow, vessel wall injury, and increased clotting tendency - known as Virchow’s triad.

Because the clot sits in a deep vein, it’s harder to feel than a superficial bruise, which is why many people ignore early signs.

Understanding Pulmonary Embolism

A PE is the result of a clot (or part of it) traveling to the lungs and blocking a pulmonary artery. When blood can’t flow past the blockage, the affected lung tissue can’t get oxygen, leading to shortness of breath, chest pain, and, in severe cases, cardiovascular collapse.

The size and position of the clot determine how serious the symptoms are. A massive PE can raise pressure in the right side of the heart, causing sudden cardiac arrest.

How DVT Turns Into PE

The journey from leg to lung follows a predictable path:

- Clot forms in a deep leg vein (DVT).

- Portions of the clot break off - these are called emboli.

- Emboli travel up the inferior vena cava, into the right atrium, then the right ventricle.

- They are pumped into the pulmonary artery and lodge in branches that match their size.

This sequence explains why anyone with an untreated DVT is at risk for a PE. The risk isn’t static; it spikes in the first two weeks after clot formation, then gradually declines as the clot stabilizes or resolves with treatment.

Risk Factors Linking the Two Conditions

Some factors increase the chance of both DVT and subsequent PE:

- Immobilisation: long flights, bed rest after surgery, or cast immobilisation.

- Genetic clotting disorders: Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, protein C or S deficiency.

- Cancer: especially pancreatic, ovarian, and lung cancers, which release pro‑coagulant substances.

- Hormonal therapy: oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy raise clotting risk.

- Obesity: excess weight compresses veins and promotes stasis.

- Smoking: damages vessel lining, encouraging clot formation.

When multiple risk factors combine, the probability of a clot forming and then travelling to the lungs rises dramatically.

Spotting the Symptoms Early

Because DVT can be silent, it’s essential to watch for subtle clues:

- Swelling in one leg (often above the ankle).

- Cramping or aching pain that worsens when standing.

- Red or discoloured skin over the affected area.

If a clot breaks free, PE symptoms appear suddenly:

- Sharp chest pain that worsens with deep breaths.

- Shortness of breath that seems out of proportion to activity.

- Rapid heartbeat, feeling faint, or coughing up blood‑tinged sputum.

Any combination of these signs warrants immediate medical attention.

Diagnosing DVT and PE

Doctors rely on imaging and blood tests to confirm both conditions.

- Compression ultrasoundA non‑invasive scan that compresses the vein to see if a clot is present is the first‑line tool for DVT.

- The D‑dimer testA blood test that measures fibrin degradation products, elevated when clots form helps rule out DVT/PE when negative.

- For suspected PE, the gold standard is a CT pulmonary angiographyA CT scan that visualises the pulmonary arteries and any blockages. V/Q scans and bedside echocardiography are alternatives when CT isn’t feasible.

Prompt imaging not only confirms the diagnosis but also guides the urgency of treatment.

Treatment Options and Prevention

The primary goal is to stop the clot from growing, prevent new clots, and reduce the chance a clot will travel to the lungs.

Common approaches include:

- Anticoagulants: medications such as warfarin, heparin, and newer direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like apixaban or rivaroxaban thin the blood, allowing the body’s natural processes to dissolve the clot.

- Thrombolysis: in severe PE, clot‑busting drugs (tPA) may be administered to quickly reopen the blocked artery.

- Mechanical retrieval: interventional radiology can physically pull out large emboli via catheter.

- Compression stockings: graduated‑pressure stockings reduce venous stasis in the legs and lower the risk of DVT recurrence.

- Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter: a small metal mesh placed in the IVC catches emboli before they reach the heart, used when anticoagulation is contraindicated.

Prevention focuses on lifestyle and medical measures:

- Stay active - short walks every two hours during long trips.

- Maintain a healthy weight and quit smoking.

- Hydration: keep blood volume adequate during flights or surgeries.

- Discuss prophylactic anticoagulation with your doctor if you’re undergoing major surgery or have a known clotting disorder.

DVT vs PE - Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) | Pulmonary Embolism (PE) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Deep veins of the leg or pelvis | Pulmonary arteries in the lungs |

| Typical symptoms | Leg swelling, pain, warmth, discoloration | Sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, rapid heart rate |

| Primary diagnostic test | Compression ultrasound | CT pulmonary angiography |

| Immediate danger level | Moderate - risk of embolisation | High - can cause cardiac arrest |

| Standard treatment | Anticoagulation, compression stockings | Anticoagulation, possible thrombolysis |

Living With the Risks - Practical Tips

Even after treatment, staying vigilant pays off.

- Carry an alert card or bracelet noting any clotting disorders.

- Schedule regular follow‑ups to monitor anticoagulant levels, especially if you’re on warfarin.

- Know how to self‑inject low‑molecular‑weight heparin if you’ll be travelling for weeks.

- Educate family members on the signs of PE - a sudden collapse can be fatal if not treated within minutes.

With the right precautions, most people recover fully and avoid future clots.

Can a small DVT still cause a deadly PE?

Yes. Even tiny clots can break off and travel to the pulmonary arteries. The risk is highest in the first two weeks after the clot forms, which is why early treatment is critical.

Do compression stockings prevent PE?

They don’t stop an existing clot from moving, but they reduce leg stasis, lowering the chance that a new DVT will form and later become a PE.

Is it safe to travel by plane after a DVT diagnosis?

Travel is possible if you’re on anticoagulants, wear compression stockings, and move your legs every hour. Always get clearance from your physician before long flights.

What are the warning signs of a massive PE?

Sudden collapse, severe shortness of breath, chest pain that worsens with breathing, fainting, and a rapid, weak pulse. Call emergency services immediately - time is vital.

Can I stop anticoagulants once my clot dissolves?

Your doctor will decide based on clot size, underlying risk factors, and bleeding risk. Many patients continue low‑dose anticoagulation for months to a year to prevent recurrence.

Jasmina Redzepovic

October 20 2025Virchow's triad—stasis, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulability—constitutes the mechanistic backbone of DVT pathogenesis, and any lapse in prophylactic protocols amplifies the embolic cascade.