Climate Risk Heart Calculator

Environmental Risk Factors

Risk Assessment

Enter your information to see your cardiovascular risk level.

Rising temperatures, smoggy skies, and more frequent storms aren’t just uncomfortable - they’re turning the heart into a pressure cooker. Researchers now link the planetary shifts of climate change directly to a jump in coronary artery disease cases, and the numbers are hard to ignore.

What is coronary artery disease?

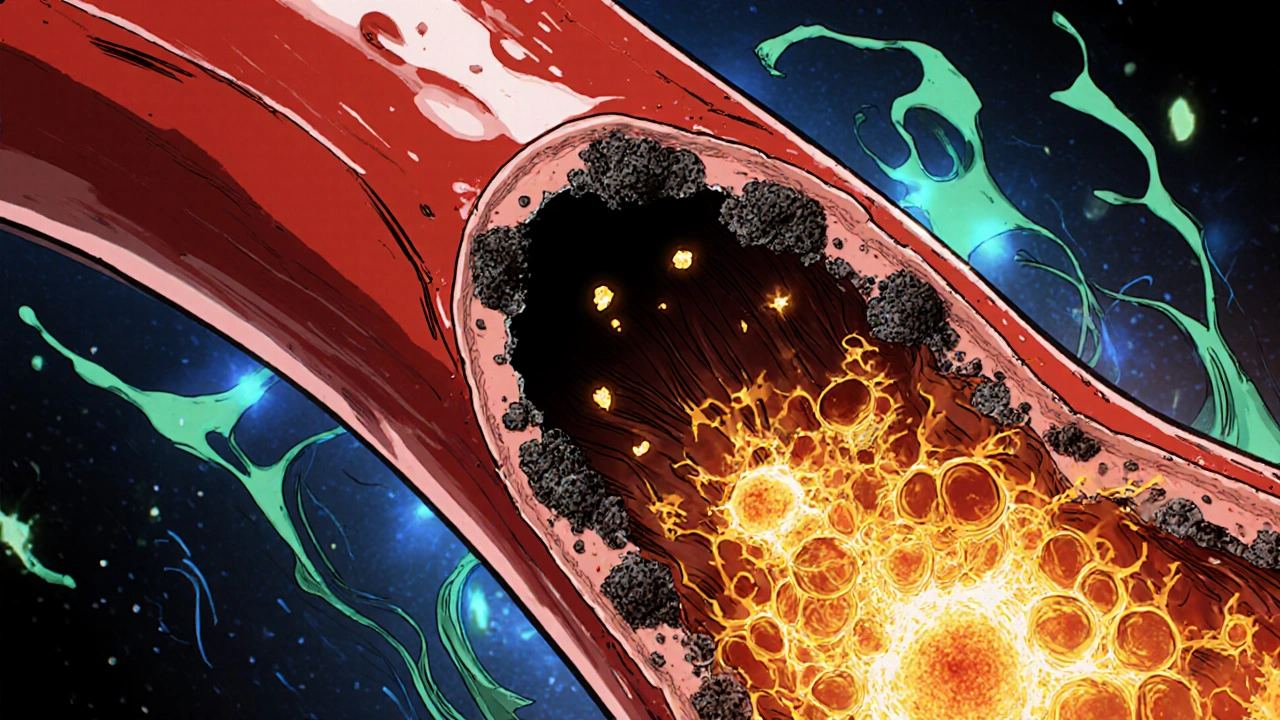

Coronary artery disease is a condition where plaque builds up inside the coronary arteries, narrowing the channels that deliver oxygen‑rich blood to the heart muscle. It’s the leading cause of heart attacks worldwide, responsible for about 9 million deaths each year, according to the World Health Organization. The classic culprits - high cholesterol, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle - still matter, but a new player is entering the arena: the changing climate.

Climate change in a nutshell

Climate change refers to long‑term shifts in temperature, precipitation, and weather patterns caused largely by human‑driven greenhouse‑gas emissions. Since the industrial era, average global temperatures have risen by roughly 1.2°C, sea levels have climbed, and extreme weather events have become the new normal.

Air pollution: the invisible cardiac toxin

Air pollution is the presence of harmful substances like particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere. Numerous cohort studies show that each 10 µg/m³ increase in PM2.5 raises the risk of coronary events by about 13 %. The tiny particles slip into the bloodstream, trigger inflammation, and accelerate plaque formation.

Heat waves and heart strain

Heat waves are extended periods of excessively high temperatures, often accompanied by high humidity. During a heat wave, the body works harder to cool down, raising heart rate and blood pressure. A 2022 analysis of U.S. hospitals found a 7 % surge in heart‑attack admissions on days where the temperature topped 35 °C (95 °F).

Extreme weather events: sudden shocks to the cardiovascular system

Storms, floods, and hurricanes bring more than property damage. The stress of evacuation, loss of medication access, and disrupted medical services can precipitate acute coronary syndromes. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, Puerto Rico saw a 15 % spike in cardiovascular mortality within three months.

How climate stress translates into artery damage

Three biological pathways connect climate factors to coronary artery disease:

- Inflammation is the body’s immune response that, when chronic, damages blood vessels and fuels plaque growth.

- Oxidative stress is an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants, leading to endothelial injury.

- Blood pressure is the force exerted by circulating blood on artery walls; sustained elevations strain the coronary circulation.

All three accelerate atherosclerosis - the slow buildup of fatty deposits that characterizes coronary artery disease. Heat, pollutants, and stress boost inflammatory cytokines, increase reactive oxygen species, and raise systolic pressure, creating a perfect storm for plaque rupture.

What the data say

Recent large‑scale studies provide the hard evidence:

- In the Global Burden of Disease 2023 report, climate‑related air pollution accounted for 1.2 million premature coronary deaths, a 19 % increase from 2010.

- A European cohort of 500,000 adults tracked from 2005‑2022 showed a 22 % higher incidence of myocardial infarction among those living in regions with a >2 °C rise in average summer temperature.

- The INTERHEART study added a climate‑exposure questionnaire and found that participants who reported frequent heat‑wave exposure had an odds ratio of 1.35 for acute coronary events, even after adjusting for smoking and cholesterol.

These numbers aren’t speculative - they come from peer‑reviewed journals like The Lancet Planetary Health and the American Heart Association Journal.

Traditional vs. climate‑related risk factors

| Category | Specific Factor | Typical Impact (Relative Risk) |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional | High LDL cholesterol | 1.8‑2.2× |

| Traditional | Smoking | 2.0‑2.5× |

| Climate‑related | Long‑term PM2.5 exposure | 1.3‑1.6× |

| Climate‑related | Frequent heat‑wave days | 1.2‑1.4× |

| Climate‑related | Extreme‑weather stress (e.g., post‑disaster) | 1.3‑1.5× |

The table shows that while classic factors still carry higher odds, climate‑related exposures add a measurable, independent risk that piles onto the baseline.

Public‑health implications

If climate change pushes even a modest fraction of the population into higher coronary risk, the health system faces millions of extra admissions. Policymakers can act on two fronts:

- Reduce emissions - cleaner energy, tighter vehicle standards lower ambient PM2.5, directly cutting the cardiac toll.

- Adapt health services - heat‑alert systems, mobile clinics after disasters, and real‑time air‑quality dashboards help clinicians pre‑empt spikes in heart attacks.

Community‑level interventions, such as planting trees in urban neighborhoods, simultaneously cool the microclimate and filter pollutants, delivering a double benefit.

What individuals can do today

Even without changing the planet, you can shield your heart:

- Check the daily air‑quality index (AQI). On days above 100, limit outdoor exercise or wear a high‑efficiency mask.

- Stay hydrated and avoid strenuous activity when temperatures exceed 30 °C (86 °F). Cool down with shade or air‑conditioned spaces.

- Keep blood‑pressure meds handy during extreme‑weather events. Have a small emergency kit with prescriptions, a charger, and a list of local clinics.

- Adopt a heart‑healthy diet rich in antioxidants (berries, leafy greens). Antioxidants combat oxidative stress triggered by pollutants.

- Advocate for greener policies in your city - public transport upgrades, clean‑energy incentives, and robust emergency‑response plans all reduce the climate‑cardiac link.

These steps won’t eliminate risk, but they can blunt the added pressure that climate change places on your coronary arteries.

Key takeaways

- Climate change isn’t just an environmental issue; it’s a growing cardiovascular threat.

- Air pollution, heat waves, and extreme weather each raise the odds of coronary artery disease through inflammation, oxidative stress, and higher blood pressure.

- Large‑scale studies confirm a 10‑20 % increase in heart‑attack rates linked to climate‑related exposures.

- Policy actions that cut emissions and improve emergency health services can curb future cardiac deaths.

- Individuals can protect themselves by monitoring air quality, staying cool, staying hydrated, and maintaining a heart‑healthy lifestyle.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does air pollution directly affect my heart?

Fine particles (PM2.5) can penetrate deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream, and trigger systemic inflammation. This inflammation destabilizes plaque in coronary arteries, making heart attacks more likely.

Are heat waves dangerous for people without heart disease?

Yes. Heat forces the heart to pump faster to dissipate heat, raising blood pressure. In susceptible individuals, this extra workload can precipitate a first‑time coronary event.

Can I still exercise outdoors on a mildly polluted day?

If the AQI is below 100, moderate activity is generally safe. On higher AQI days, switch to indoor cardio or wear a certified N95 mask to filter particles.

What role do antioxidants play in this context?

Antioxidants neutralize free radicals produced by oxidative stress, helping protect the lining of blood vessels from damage caused by pollutants and heat‑induced metabolic stress.

Is there a geographic hotspot for climate‑linked heart disease?

Urban centers in hot, high‑pollution regions-like Delhi, Los Angeles, and parts of the Middle East-show the highest combined exposure to heat and particulate matter, correlating with elevated coronary event rates.

Gary Marks

October 22 2025Wow, this article tries to mash together climate nerd‑talk and heart disease like it’s a smoothie, but the result is a half‑baked mess that reads like a bad horror flick. First off, the “pressure cooker” metaphor is tired and does nothing except scream for attention. The authors toss in statistics without any real context, as if numbers alone can paint a picture of causality. They ignore the fact that coronary artery disease has been killing people long before we started measuring CO₂ levels. Sure, air pollution is bad, but blaming it for every uptick in heart attacks is a simplistic scapegoat that shifts focus from personal responsibility. The heat‑wave data cited are cherry‑picked from a single U.S. study, ignoring many regions where temperatures have risen without a corresponding spike in cardiac events. And let’s not even get started on the “extreme weather shock” argument; stress is a vague, catch‑all term that the authors wield like a magic wand. They also claim oxidative stress from pollutants is a major driver, yet provide no mechanistic evidence beyond a handful of animal studies. The table comparing traditional and climate‑related risk factors is presented with the same reverence as a medical textbook, but the relative risks listed are modest at best. Moreover, the article’s tone is alarmist, pushing a political agenda under the guise of science. It’s like trying to sell a heart‑shaped popcorn machine at a climate rally – it looks flashy but serves no real purpose. While the call for greener policies is noble, the piece suggests that without them, the world is doomed to a cardiac apocalypse, which is hyperbolic. The authors also neglect socioeconomic factors that heavily influence both exposure to pollutants and heart disease outcomes. If you dig into the cited Lancet paper, you’ll find the authors themselves caution against over‑interpreting the data. Instead of a balanced discussion, this post is a one‑sided manifesto that panders to climate alarmism. In short, it’s a glossy PR piece masquerading as rigorous research, and it does a disservice to both cardiology and climate science.