Elderly Anemia Risk Assessment

Answer the following questions to assess your risk for anemia. Each "Yes" adds 1 point to your risk score.

Your risk assessment result will appear here after answering the questions.

Quick Takeaways

- About 30% of people over 65 have some form of anemia.

- Common triggers include iron deficiency, vitamin B12 shortfall, and chronic diseases.

- Early signs are fatigue, shortness of breath, and reduced exercise tolerance.

- Management mixes diet changes, targeted supplements, and, when needed, medical therapies like erythropoietin.

- Untreated anemia increases fall risk, cognitive decline, and hospital admissions.

Imagine feeling constantly wiped out, even after a full night’s sleep. For many seniors, that’s not imagination-it’s a daily reality caused by elderly anemia. Roughly one in three adults over 65 grapple with low red‑blood‑cell counts, and the consequences stretch far beyond simple tiredness. This guide breaks down why the condition is so common in older adults, how to spot it early, and what practical steps can keep it under control.

What Is Anemia in Older Adults?

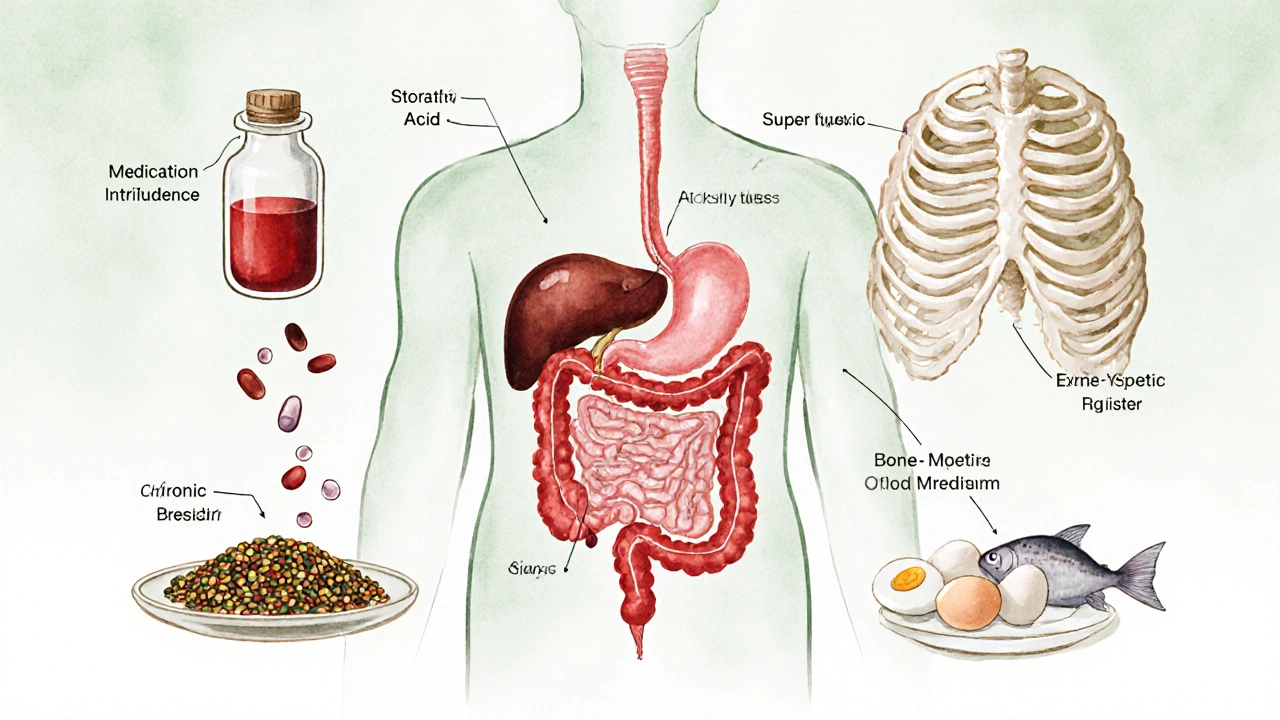

Anemia in the elderly refers to a reduced concentration of hemoglobin or red blood cells in people aged 65 and older, impairing oxygen transport throughout the body. It isn’t a single disease but a symptom of many underlying problems-nutrient gaps, chronic inflammation, bone‑marrow issues, or medication side effects. Because the aging body processes nutrients and produces blood differently, the same lab values that signal mild anemia in a younger adult can have serious functional impacts in a senior.

Why Seniors Are More At Risk

Several age‑related changes pile up, creating a perfect storm for low blood counts:

- Reduced dietary intake: Diminished appetite, chewing difficulties, or limited access to nutrient‑dense foods lower iron and vitamin B12 consumption.

- Malabsorption: Stomach acidity drops with age, hindering iron absorption; atrophic gastritis can prevent B12 uptake.

- Chronic illnesses: Heart failure, kidney disease, and rheumatoid arthritis trigger anemia of chronic disease a form of anemia driven by inflammation and altered iron metabolism.

- Medication interference: NSAIDs cause gastrointestinal bleeding; proton‑pump inhibitors reduce acid needed for iron absorption.

- Bone‑marrow decline: Conditions like myelodysplastic syndrome a group of disorders where the marrow produces faulty blood cells become more common after age 70.

Spotting the Signs Early

Older adults often attribute fatigue to “just getting old,” but certain clues point straight to anemia:

- Persistent tiredness despite adequate sleep.

- Shortness of breath during routine tasks such as climbing a single flight of stairs.

- Pale skin, especially on the face, gums, or nail beds.

- Dizziness or light‑headedness when standing up quickly.

- Cold hands and feet, or an inexplicable craving for ice (pagophagia).

When these symptoms appear together, a simple blood test can confirm the diagnosis.

How Doctors Diagnose the Problem

Standard blood work includes a complete blood count (CBC) that reports hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red‑cell indices. If anemia is confirmed, further tests pinpoint the cause:

- Serum ferritin and iron studies to assess dietary iron the amount of iron stored in the body, usually measured by ferritin levels.

- Vitamin B12 and folate levels to rule out deficiency‑related anemia.

- Reticulocyte count to gauge bone‑marrow response.

- Inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR) when chronic disease is suspected.

- Kidney function tests, because reduced erythropoietin production can trigger anemia.

In complex cases, a bone‑marrow biopsy may be ordered to investigate myelodysplastic syndrome or malignancy.

Managing Anemia: A Tiered Approach

Treatment starts with the simplest, least invasive options and escalates only if needed. The goal is to raise hemoglobin to a level that restores energy and reduces fall risk.

1. Nutrition First

Boosting iron‑rich foods can correct mild iron deficiency without medication. Good sources include lean red meat, fortified cereals, lentils, and dark leafy greens. Pair iron‑dense meals with vitaminC (citrus, bell peppers) to improve absorption.

For vitaminB12, incorporate animal products such as fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy. Seniors who follow vegetarian diets may need fortified plant milks or nutritional yeast.

When appetite is low, small, frequent meals fortified with powdered iron and B12 can be easier to tolerate.

2. Targeted Supplements

If dietary changes fall short, clinicians prescribe oral iron (ferrous sulfate, gluconate) or B12 tablets. Choose formulations with low gastrointestinal irritation-iron bisglycinate is gentler on the stomach.

In cases of severe deficiency or malabsorption, vitamin B12 injections intramuscular administration of cyanocobalamin to bypass the gut provide rapid correction.

Monitor serum levels every 4-6 weeks to avoid overload, which can damage organs.

3. Medical Therapies

When anemia stems from chronic disease or kidney failure, oral supplements may be ineffective. Options include:

- Erythropoietin‑stimulating agents (ESA) synthetic hormones that encourage the bone marrow to produce red blood cells, commonly used for anemia of chronic kidney disease.

- Intravenous iron for patients who cannot tolerate oral forms or need rapid repletion.

- Blood transfusions in emergencies or when hemoglobin falls below 7-8g/dL, but they carry risks like fluid overload and infection.

ESA therapy requires careful dosing and regular blood pressure checks, as it can increase clotting risk.

4. Lifestyle Adjustments

Exercise, even light walking or chair‑based strength training, boosts circulation and can improve red‑cell production. Encourage seniors to stay active within safe limits.

Hydration helps maintain blood volume, and adequate sleep supports overall marrow health.

Preventing Complications

Untreated anemia leads to a cascade of issues:

- Falls and fractures: Reduced oxygen to muscles impairs balance.

- Cognitive decline: Brain cells receive less oxygen, affecting memory and attention.

- Heart strain: The heart works harder to deliver oxygen, worsening heart failure.

- Hospital readmissions: Low hemoglobin is a predictor of longer stays.

Regular screening-once a year for adults over 65, or more often for those with chronic illnesses-helps catch anemia before it spirals.

Everyday Tips for Seniors and Caregivers

- Schedule an annual CBC with your primary care provider.

- Keep a simple food log to ensure iron‑rich meals appear at least three times a week.

- Set medication reminders; avoid taking iron supplements with coffee or calcium, which impede absorption.

- Watch for warning signs: sudden fatigue, shortness of breath, or unexplained dizziness.

- Stay active-short walks, gentle stretching, or water aerobics improve blood flow.

Comparison of Common Anemia Types in Seniors

| Type | Primary Cause | Typical Lab Pattern | First‑Line Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron‑deficiency anemia | Insufficient iron intake or chronic blood loss | Low ferritin, low serum iron, high TIBC | Dietary iron + oral iron supplement |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | Poor absorption (atrophic gastritis, meds) | Low B12, elevated methylmalonic acid | Monthly B12 injections or high‑dose oral B12 |

| Anemia of chronic disease | Inflammation from chronic conditions | Low iron, normal/high ferritin, low TIBC | Treat underlying disease; consider ESA |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | Bone‑marrow dysfunction, often age‑related | Macrocytic anemia, abnormal cell morphology | Supportive care, low‑dose ESA, possible transfusion |

Frequently Asked Questions

How is anemia different from normal aging?

Aging can cause a mild drop in hemoglobin, but true anemia is defined by specific lab thresholds (e.g., < 12g/dL for women, < 13g/dL for men). The symptoms are more pronounced and can be treated.

Can iron supplements cause constipation?

Yes, especially ferrous sulfate. Switching to a chelated form or taking the dose with meals and plenty of water can lessen the issue.

Is it safe for seniors to take high‑dose vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 has a very low toxicity risk. Doses up to 1000µg daily are generally considered safe, but follow your doctor’s recommendation.

When is a blood transfusion necessary?

Transfusion is usually reserved for hemoglobin below 7g/dL or when severe symptoms (e.g., chest pain, acute heart failure) appear despite other treatments.

How often should seniors get screened for anemia?

A yearly CBC is advised for anyone over 65. Those with chronic kidney disease, inflammatory disorders, or a history of anemia should have tests every 3-6 months.

Understanding and tackling anemia in older adults isn’t just about boosting numbers on a lab report-it’s about reclaiming energy, independence, and quality of life. By staying alert to risk factors, catching symptoms early, and following a layered treatment plan, seniors can keep anemia from stealing their spark.

Anna Cappelletti

October 9 2025Hey folks, just wanted to say that taking a quick self‑check for anemia symptoms is a great first step. Even if you feel a little off, the questionnaire can point you toward a doctor. Remember, staying active and eating iron‑rich foods like spinach can make a big difference. Keep an eye on your energy levels and don’t hesitate to ask your healthcare provider for a blood test if you’re unsure. You’ve got this!