Barrett’s Esophagus isn’t just a mouthful of a medical term-it’s a silent warning sign that could save your life. If you’ve had acid reflux for years, especially if it’s daily or worse, your esophagus might be changing in ways you can’t see. That change is Barrett’s Esophagus: when the normal lining of your esophagus, which should look like tough, flat skin, gets replaced by a smoother, more intestine-like tissue. It doesn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of years of stomach acid burning the lower esophagus. And while most people with reflux never develop it, those who do face a real, measurable risk of turning this condition into esophageal cancer.

How Bad Is the Risk Really?

The scary part? Esophageal adenocarcinoma, the cancer that can come from Barrett’s, has a 5-year survival rate of only 20% if caught late. But here’s the flip side: if you catch the changes early-before cancer even starts-you can reduce that risk to under 5%. That’s why knowing your risk matters.

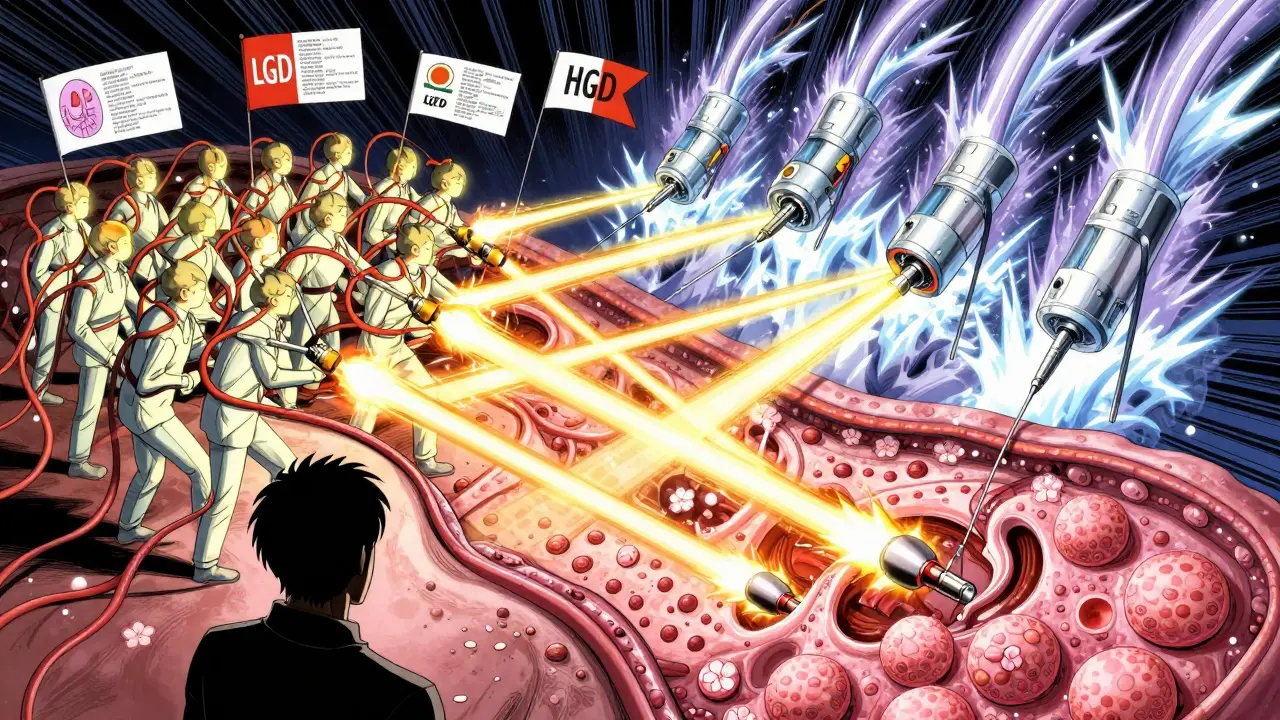

Not everyone with Barrett’s is headed for cancer. For most people without dysplasia (meaning no abnormal cell changes), the chance of developing cancer is about 0.2% to 0.5% per year. That sounds low, but over 10 years, that adds up. Now, if you have low-grade dysplasia (LGD), your risk jumps to 5 times higher. And if you’ve been told you have high-grade dysplasia (HGD)? That’s a red flag. The risk of cancer jumps to 23-40% per year. That’s not a slow burn-it’s a fire.

Some people are at higher risk just by who they are. Men are 2 to 3 times more likely than women to develop Barrett’s. If you’re over 50, white, have a long history of GERD (5+ years), smoke, or carry extra weight around your middle, your odds go up even more. Family history plays a role too-if a close relative had Barrett’s or esophageal cancer, your risk is 23% higher. And here’s something surprising: alcohol doesn’t raise your risk. But caffeine? Weekly intake has been linked to higher progression rates. So if you’re downing coffee or soda daily, it’s worth considering.

What Happens If Dysplasia Is Found?

For years, the standard was to just watch and wait-repeat endoscopies every year or two, take biopsies, and hope nothing changed. But that’s changing fast. Now, experts agree: if you have confirmed low-grade or high-grade dysplasia, you should be offered treatment. Not because every case will turn to cancer, but because the consequences of waiting are too severe.

Dr. Prateek Sharma, a leading voice in this field, says it plainly: “For patients with confirmed low-grade dysplasia, endoscopic ablation reduces progression risk to adenocarcinoma by 90% compared to surveillance alone.” That’s not a small win. That’s life-saving.

But there’s a catch. Not all dysplasia is created equal. Studies show that community pathologists agree on a diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia only about 55% of the time compared to expert GI pathologists. That means some people are being told they have dysplasia when they don’t-and getting unnecessary treatments. Others are being told they’re fine when they’re not. That’s why getting a second opinion from a center that specializes in Barrett’s is critical.

The Ablation Options: What Works, What Doesn’t

Today, there are three main ways to remove or destroy the abnormal tissue in Barrett’s Esophagus. Each has pros, cons, and places where it shines.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) - The Gold Standard

RFA is the most common treatment. It uses heat delivered through a balloon or catheter to zap the abnormal lining. Think of it like a controlled burn-just enough to destroy the bad cells without damaging the deeper layers of the esophagus. The body then regenerates healthy tissue.

It’s effective. In major studies, RFA cleared intestinal metaplasia (the abnormal tissue) in 77.4% of cases and dysplasia in 87.9% after one year. By 2023, it was used in 78% of all ablation procedures. The HALO360 and HALO90 systems are the most common tools. One session usually isn’t enough-most patients need 2 to 3 treatments spaced a few months apart.

But it’s not perfect. About 6% of patients develop strictures-narrowing of the esophagus that makes swallowing hard. That often requires dilation, which can be uncomfortable. One Reddit user described it: “The chest pain during dilation was worse than the original Barrett’s symptoms.” Still, for most, the trade-off is worth it.

Cryoablation - The Cooler Alternative

Cryoablation uses extreme cold-nitrous oxide chilled to -85°C-to freeze and kill abnormal cells. It’s newer, but gaining ground fast. In the 2021 CRYO-II trial, it achieved 82% eradication of dysplasia. It’s especially useful for patients who already have strictures, because it’s gentler on the tissue. Stricture rates are lower-around 2.8% compared to 6.2% with RFA.

One big advantage? Less pain after the procedure. And some patients report that their reflux symptoms improve after treatment. One user on Inspire said: “Two years after cryoablation, my chronic cough from reflux disappeared completely.”

But cryoablation isn’t as effective at erasing the underlying metaplasia. One head-to-head study found RFA cleared metaplasia in 91.5% of cases versus 65.2% for cryoablation. So if your goal is complete eradication, RFA still leads.

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) and EMR - Less Common Now

PDT used to be popular. It involved injecting a light-sensitive drug, waiting 48 hours, then shining a laser to destroy the abnormal tissue. It worked-77% of dysplasia was cleared. But it came with a big downside: you had to avoid sunlight for weeks. Skin burns, blistering, and a 17% risk of strictures made it a last-resort option. Today, it’s rarely used.

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) is different. It doesn’t zap-it removes. A small tool lifts the abnormal patch and cuts it out. It’s great for visible lesions, especially if there’s a nodule or bump. EMR has a 93% success rate for removing small lesions. But it’s invasive. Bleeding happens in 5-10% of cases. Perforation (a hole in the esophagus) is rare but serious-about 2% risk.

What Happens After Ablation?

Treatment doesn’t end when the procedure does. You’ll need to keep taking high-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), like esomeprazole 40mg twice daily. Why? Because if acid keeps coming back, the abnormal tissue can return. A 2023 study showed that with high-dose PPIs, recurrence dropped to 8.3% over three years-compared to 24.7% with standard doses.

You’ll also need follow-up endoscopies. Usually, one at 3 months, then another at 12 months, then every 1-3 years if things look clean. Biopsies are still needed-even after ablation, you’re not “cured.” You’re in remission.

And here’s something many don’t tell you: insurance coverage varies. In the U.S., RFA costs about $12,450 per session. Cryoablation is cheaper-around $9,850. But because cryoablation often needs more repeat sessions, the 5-year cost ends up being almost the same. Still, for people without insurance or with high deductibles, that difference matters.

What About People Without Dysplasia?

This is where things get controversial. About 70% of Barrett’s patients don’t have dysplasia. Should they get ablation? The answer is no-unless they have other very high-risk features.

Dr. Stuart Spechler points out that 25-30% of ablation procedures are done on people who don’t need them. Medicare data shows many patients are getting treated for non-dysplastic Barrett’s, often because of misdiagnosis or fear. That’s a problem. Ablation isn’t risk-free. It can cause strictures, bleeding, and pain. You don’t want to trade one problem for another.

The current guideline? Surveillance. Endoscopy every 3-5 years for non-dysplastic Barrett’s. If dysplasia shows up, then you act.

The Future: AI, Biomarkers, and Better Access

The field is moving fast. In 2024, Google Health tested an AI tool that detected dysplasia with 94% accuracy-far better than the 78% rate of community endoscopists. That could mean fewer missed cases.

Another promising area? Biomarkers. A simple blood or saliva test that checks for TFF3 methylation might soon tell us who’s at real risk-without needing repeated biopsies. Early studies suggest it could cut unnecessary procedures by 30%.

But access remains a huge issue. In rural areas, only 42% of practices offer ablation. In urban academic centers, it’s 85%. That gap means people in small towns are 2.3 times more likely to die from esophageal cancer than those in cities. This isn’t just a medical problem-it’s a health equity problem.

What Should You Do?

If you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s Esophagus:

- Confirm the diagnosis with an expert GI pathologist.

- Get a high-definition endoscopy with narrow-band imaging to spot subtle changes.

- If dysplasia is confirmed, discuss ablation. RFA is the first choice for most. Cryoablation is a solid alternative, especially if you’ve had prior strictures.

- Take high-dose PPIs daily. Don’t skip them.

- Quit smoking. Lose weight if you’re overweight. Cut back on caffeine.

- Don’t rush into ablation if you have no dysplasia. Watchful waiting is still the right path.

Barrett’s Esophagus isn’t a death sentence. It’s a warning light. And with the right care, you can turn it off.

Joanne Tan

February 12 2026okay so i had acid reflux for like 8 years and never thought twice about it... then one day my dr said "hey u have barrett's" and i thought she meant like a new brand of jeans lmao. but after reading this, i’m scheduling an endo next week. no more ignoring the burn. 🙌